Although various forms of eye trauma are commonly seen in our clinics, few incite as much stress and anxiety as open globe injuries.

Young ophthalmologists are more likely to encounter open globes, since we are more frequently on call at local emergency rooms and may be more available to receive urgent add-on patients. Although this can be stressful, you will need to act quickly because repairing open globes within 24 hours of injury may improve visual outcomes and prevent infection.

Here are a few pearls to help guide you through the evaluation and management of open globes.

1. Evaluation

Performing an ophthalmic evaluation prior to surgical repair is important and can aid in surgical planning. However, obtaining a thorough exam can be tricky, given the level of anxiety and pain that patients may experience. Take care not to extrude intraocular contents by pressing on the eye or inducing valsalva in the patient. The patient should wear eye protection at all times unless being examined or undergoing a procedure. Consider adding antiemetics and pain medicine to make the patient more comfortable. Additionally, avoid manipulating vitreous or intraocular contents that may have been expelled from the eye which may be stuck to eyelashes or other structures.

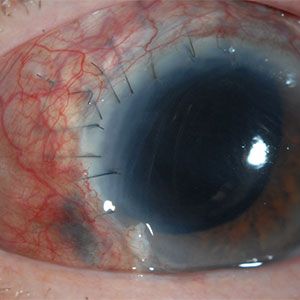

A Zone 1 corneal laceration in post-operative week three caused by a fish hook injury. The cornea has been repaired with two 10-0 nylon sutures, and the patient ultimately obtained 20/30 vision. Image courtesy of Dr. Grayson Armstrong and Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

Whenever possible, perform a slit lamp or bedside examination, and draw the injury as you see it. Drawing the ocular pathology can be helpful in developing a plan for surgical repair. Additionally, look for clues that may indicate the location of the injury. A corneal laceration or a peaked pupil is easy to identify, but a deep anterior chamber, vitreous hemorrhage, or dense subconjunctival hemorrhage may indicate that a scleral rupture or laceration has occurred. B-scan should be avoided in most cases, as this can expulse intraocular contents. In rare cases, this can be used to localize or rule out posterior pathology if there is no view.

Lastly, I recommend a CT scan of the brain and orbits without contrast with thin cuts in all cases to rule out occult intraocular foreign bodies.

2. Counseling Patients and Managing Expectations

Patients experiencing open globe injuries are likely having one of the worst days of their lives. Be empathic during this time of crisis. Although you may feel compelled to give patients hope for complete visual recovery, it is important to let patients know that it is difficult to accurately prognosticate their clinical outcome. Inform patients that the goal of the first surgery is to close the eye, and that their vision will likely still be poor after the initial repair. Informing them that there may be a need for future surgeries to try and improve their vision is helpful in setting expectations.

Part of this conversation should include signing the consent form for surgery. In ruptured globe surgery consider including evisceration and enucleation as possibilities, although they are rarely performed in a primary repair. Use the “teach-back” method to ensure the patient understands.

Patients will often ask about their future visual prognosis. Fortunately, you can use the Ocular Trauma Score to predict final visual acuity in the patient’s injured eye.

3. Preoperative Planning

No matter how thorough your preoperative ophthalmic evaluation was, you should prepare to encounter the unexpected in the OR. Ocular wounds may hide underneath blood clots, vitreous or conjunctiva, and the true extent of the injury may not be known until you find yourself scrubbed in.

Make sure you ask for any and all instrumentation that you think you might possibly need, including Weck-Cel surgical eye spears, cotton tip applicators, Steri-Strips, a paracentesis blade, Castroviejo suturing forceps, blunt Westcott scissors, curved Stevens scissors, iris and cyclodialysis spatulas, fine needle holders, tying forceps (curved and straight), Vannas scissors, calipers, Gass muscle hooks, a Schepens retractor and a wide range of different sutures. Depending on your preoperative evaluation, additional instruments may be needed.

It is always easier to operate on an open globe under general anesthesia if the patient’s general health will allow it. There are varying opinions about the use of 5% povidone-iodine on the open globe eye, but at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear, we use this routinely. Consider using topical moxifloxacin for surgical prep for open globes since this is common in many practice situations. We also recommend using Jaffe specula, which lifts tissue up and away from the globe, instead of using conventional specula which may push down on the eye and expulse intraocular contents. These specula are secured to the surgical drape with sterile rubber bands, which is easiest to do if you pinch the drapes and stretch the rubber bands before you apply butterfly clamps.

4. Explore and Visualize the Wound

The most important step in open globe repair is visualization of the entire wound, devoid of anything obscuring the wound edge. Corneal wounds can be difficult to visualize and repair in hypotonous (low pressure) eyes, so viscoelastic or air can be used to inflate the anterior chamber. Although air may maintain the anterior chamber, it can quickly escape through corneal wounds and deflate the eye. Alternatively, viscoelastic may extrude from wounds, be difficult to discern from vitreous, and make corneal suturing more difficult.

If creating a paracentesis, consider grasping the episclera firmly directly adjacent to where you plan on making your surgical wound to provide increased stability. Additionally, point the tip of your blade more posteriorly than you would in routine anterior segment surgery, given the hypotonous nature of the cornea.

Unlike corneal wounds, scleral wounds may be hidden beneath the conjunctiva and Tenon’s capsule and may be obscured by clot or scarred-down Tenon’s. Following a peritomy, careful dissection with Westcott scissors and curved Stephen’s scissors in the four oblique quadrants should be used to identify any scleral defect. Once identified, meticulous dissection of clot, uveal content, and scarred Tenon’s capsule will expose the true scleral edge of the wound. Without exposing the scleral wound edge, improper closure may occur and the wound is at risk of dehiscence.

5. Suturing Tips and Techniques

Proper suturing technique is critical for open globe repair. Wounds extending past the corneal limbus should be repaired by first reapproximating the limbus using 9-0 nylon suture, which promotes healing while minimizing scarring and loss of tensile strength. Corneal repair should employ 10-0 nylon suture, which should extend 90% depth. Corneal sutures closer to the visual axis should be shorter than in the periphery of the cornea, and you should take care to avoid suturing in the central visual axis if possible. Slip knots can be helpful in closing the cornea, since they allow complete repair to take place while allowing the final tension to be determined at the end of the closure. We recommend 8-0 nylon for scleral wounds.

6. Foreign Bodies

Intraocular foreign bodies carry a higher risk of endophthalmitis and poor visual outcomes. If the foreign body is in the anterior chamber, this can be easily removed during corneal or scleral globe repair. However, foreign bodies embedded in the posterior segment may require a pars plana vitrectomy and careful removal of the foreign material. Depending on your specialty and training, you may need to work alongside your colleagues to accomplish this.

7. Antibiotics, Steroids, and Cycloplegics

A Zone 2 scleral laceration seen in post-operative week six in a patient that initially suffered from uveal prolapse and lens extrusion. This was repaired with 9-0 and 10-0 nylon sutures, all of which are covered at least partially by conjunctiva and can remain in place unless they erode through the conjunctiva and become irritating to the patient. Image courtesy of Dr. Armstrong and Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

At the time of patient presentation, our institution implements 48 hours of intravenous antibiotics with good gram-positive and gram-negative coverage, including pseudomonas. Specifically, we administer intravenous vancomycin and ceftazidime. For penicillin or cephalosporin allergic patients, we instead use intravenous ciprofloxacin.

After the repair, we administer subconjunctival antibiotics and steroids, and post-operatively, we administer one week of topical antibiotic eye drops and extended use of cycloplegics until intraocular inflammation subsides. Lastly, we slowly taper topical corticosteroids over the course of weeks to months, depending on the injury. It is worth noting that there is a large range of practice patterns as it relates to systemic antibiotic administration, with some institutions preferring oral antibiotics, while others may use topical antibiotics alone.

8. Follow-Up

Close follow-up is generally recommended for open globe patients, which allows for monitoring of post-operative healing and assessing for complications. Corneal suture removal can begin to be considered six weeks post-operatively. Additional surgeries can also be considered throughout the post-operative course, including cataract removal, secondary lens placement, corneal transplantation or pars plana vitrectomy.

Further Resources

Repair of the Open Globe, American Academy of Ophthalmology

Miller SC, et al. Global Current Practice Patterns for the Management of Open Globe Injuries. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2021 Aug 18;234:259-273.

|

About the author: Grayson W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, is a comprehensive ophthalmologist and director of ophthalmic emergency services at Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston. He is a Harvard Medical School ophthalmology instructor who served as director of the eye trauma service from 2019-20. Dr. Armstrong completed his residency, chief residency and fellowship in ophthalmic telemedicine at Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Harvard Medical School. He joined the YO Info Editorial Board on Jan. 1, 2022. |